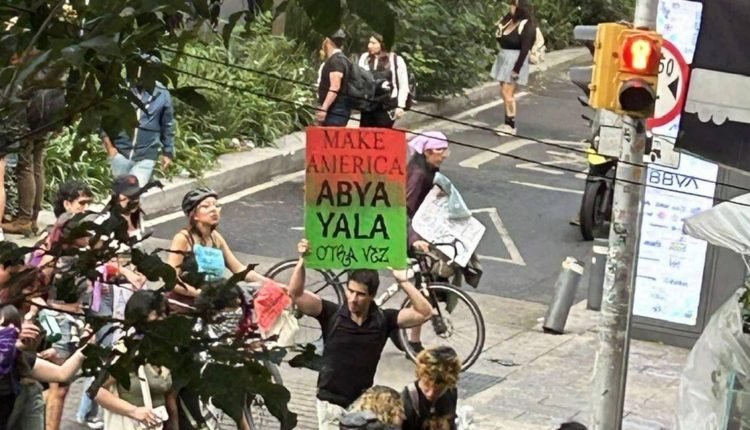

Before a wedding of two American friends, Nan Palmero was at a rehearsal evening dinner in the trendy Roma district of Mexico city when he heard a “rumbling” outside.

From the second history of the restaurant, Palmero described when he moved a large group of people through the streets and held posters and called “Gringos”.

He later learned that demonstrators smashed restaurant windows and damaged vehicles, including the new car of his friends’ wedding planner – a resident – he said.

“They destroyed their car, smashed a window, they tore down a mirror, they sprayed the side of it. It was really bad,” he said.

Palmero, an enthusiastic traveler from San Antonio, Texas, said that he had heard that an influx of digital nomads and foreign tourists in some of the city’s most popular districts increased prices.

But he did not know that the residents organized demonstrations, such as those about which he had read in Barcelona and other parts of Europe, he said.

“People … want to experience these beautiful and wonderful cultures all over the world,” he said, adding that “we influence the matter that we want to experience in a negative way.”

Protests on the advance

The protests against tourists have increased in frequency and size, since the residents who have returned a section of their cities without tourism during the pandemic or have even been exceeded on the pre-Pandemic level, said Bernadett Papp, Senior Researcher at the European Tourism Futures Institute in the Netherlands.

The residents usually choose protests instead of other forms of lobbying because they create public awareness, which leads to media reporting and social pressure for the action, she said. Barcelona and Amsterdam are examples of where this occurred, added.

Graffiti on a wall in Mexico city. In Mexico, “Gringo” is often used to refer to foreigners, especially those from the USA.

Source: Ernest Osuna

Locals also protest because they don’t know who to turn to. “Tourism public policy is very fragmented, which makes it difficult for residents to identify the corresponding decision -makers with whom they can deal with,” said Papp. “This is often reinforced by frustration and loss of faith in the government due to the perceived inactivity.”

Why tourists become targeted

The reactions of the residents tend to develop when upourism is intensified, said Tatyana Tsukanova, visiting professor and researcher at EHL Hospitality Business School.

“You can then tolerate it first Language problems, sometimes become confrontational and ultimately look for ways to adapt and push themselves For constructive changes, “she said.” And in this way, tourists often become scapegoats. “

A man ducks and a woman covers her ears, while demonstrators interrupt their meals in Barcelona on July 6, 2024.

Josep Lago | AFP | Getty pictures

In July 2024, demonstrators in Barcelona, Spain, objects, sprayed travelers sprayed with water pistols and canned food and used adhesive tape in the police style to block hotel entrances and sidewalk cafes. The news of the crowd was clear: “Tourists go home.”

Barcelona and the Spanish island of Mallorca saw water channel protesters returned in June, while, according to the Associated Press, there is in other parts of Spain, Venice, Italy and Lisbon, Portugal. Demonstrators in Barcelona triggered fireworks and opened a can of Rosa Rauchs, it said.

Travelers may be the visible factor that is to blame, but political gaps are the root of the problem, said Tsukanova.

Confrontations as tactics

Studies show that direct confrontations with tourists can make travelers feel undesirable and thus lead some to rethink travel, said Tsukanova.

However, this effect is usually short -lived, she said. According to the National Statistics Institute, the tourist arrivals in the first seven months of 2025 rose by 4.1%in the first seven months of 2025 in the first seven months of 2025.

A man argues on July 6, 2024 with demonstrators in front of a hotel in Barcelona.

Paco Freire | SOPA images | Light rocket | Getty pictures

However, protests can raise awareness of the problems with which the residents are faced, which can lead to travelers change certain behaviors, e.g. B. the selection of hotels compared to short -term rentals, she said.

But there is hardly any evidence that protests have long -term effects, said Tsukanova.

Papp said cities that react to pressure caused by protests do this with ad hoc guidelines that are more symbolic than they are meaningful.

“Such measures in turn increase social concerns and drives negative perceptions of tourism,” she said. “It’s a cycle.”

Possible solutions

In order to prevent cities that “are not made for life, but for tourism”, goals can reduce short -term rental rental and impose significantly higher taxes for tourists, said Lionel Saul, who visited the lecturer at EHL Hospitality Business School.

While academics develop ideas for “regenerative travel” – a form of tourism that helps the locals and does not disabled, cities should include local communities in tourism development, he said.

Doug Lansky, a traveler and more often speaker about the development of tourism, agreed and said that local voices often lack critical discussions, which in the long run violates the goals.

“If these residents had a place at the table – at every table – where they felt that they were heard on site, they would not have to march on the streets,” he said.

Lansky is a supporter of “managed tourism”, which borders such as time -controlled entries for attractions, visitor caps and the restriction, not the removal of short -term rental markets, citing the restrictions.

The compromise is less coincidence than travelers in the past.

“It’s not so much fun … You won’t waste your day when you stand in line,” he said. But “everything will benefit.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.